10.6 FINITE-STATE MACHINES (AUTOMATA)

![]()

INTRODUCTION |

If you want to investigate which problems a computer can generally solve, you first have to define what exactly a computing machine is. The famous mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing published a study on this subject in 1936, long before a programmable digital computer even existed. The Turing machine, which was named after him, gradually runs programmatically through individual states. It does this on the basis of input values that it reads from a tape, and again writes output values onto the tape. This basic notion about how the computer functions are still valid today because each processor is actually a Turing machine that runs state by state at the ticks of a clock. However, state machines that can be modeled using transition graphs are better suited for practical applications. Because there is a finite number of states, they are called finite-state machines.

|

THE ESPRESSO MACHINE AS A MEALY MACHINE |

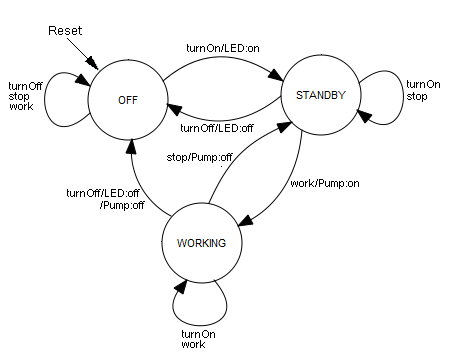

You are bound to encounter many devices and machines that you can regard as automata every single day. Automata include devices such as vending machines, washing machines, ATMs, and many others. As an engineer and computer scientist you develop such machines with the clear understanding that these perform their task in such way that they move from the current state to a successor state, depending on the sensor data and the operation of the buttons and switches. You call these the inputs of the automaton. Depending on the input values, the automaton operates certain actuators at each transition, such as motors, pumps, lights, etc. These are the outputs of the automaton. In this example, you will develop an espresso machine that has 3 states: It can be turned off (OFF), it can be enabled and ready for operation (STANDBY) and it can be actively pumping water to make an espresso (WORKING). There are 4 push buttons available that allow you to operate the machine: turnOn, turnOff, work, and stop. Although you can describe the operation of an espresso machine in words, it becomes much clearer if you draw an transition graph. For this, you illustrate the states as circles and the transitions as arrows that you can denote with the inputs/outputs. It is also important to determine which initial state the automaton is in when you connect it to the power line. Since any key can be pressed in each state, all inputs have to be possible at every state. If no action is performed, the output is omitted. Transition graph:

You can also record the behavior in a table in which you specify for each state s and each input t the successor state s'. You denote the initial state with a star. Transition table:

In mathematical terms, you can say that the successor state s' is a function of the current state s and the input t: s' = F(s, t). You call F the transitional function. You can also record the outputs belonging to each state and input: Output table:

Here too, you can say mathematically that the output g is a function of the current state s and the input t: g = G(s, t). G is called the output function. |

MEMO |

|

Together the states (with a labeled initial state), input values, and output values, as well as the transitional functions and output functions, form a so-called Mealy machine. |

IMPLEMENTING THE ESPRESSO MACHINE WITH STRINGS |

A key press should trigger the transition from one state to the next. The respective key, one of the 4 cursor keys, specifies the input value. The implementation is quite straightforward: The program waits on a key entry in an endless event loop with getEntry(). With the return value, the current state is changed according to the transition table and the outputs are given according to the output table. from gconsole import * def getEntry(): keyCode = getKeyCodeWait() if keyCode == 38: # up return "stop" if keyCode == 40: # down return "work" if keyCode == 37: # left return "turnOff" if keyCode == 39: # right return "turnOn" return "" state = "OFF" # Start state makeConsole() while True: gprintln("State: " + state) entry = getEntry() if entry == "turnOff": if state == "STANDBY": state = "OFF" gprintln("LED off") if state == "WORKING": state = "OFF" gprintln("LED and pump off") elif entry == "turnOn": if state == "OFF": state = "STANDBY" gprintln("LED enabled") elif entry == "stop": if state == "WORKING": state = "STANDBY" gprintln("Pumpe off") elif entry == "work": if state == "STANDBY": state = "WORKING" gprintln("Pumpe enabled")

|

MEMO |

|

Only the events that lead to a change of state or generate an output are treated in the event loop. With makeConsole() you create a simple input / output window, which allows the entry of individual keyboard characters (without subsequent <return>) . The call getKeyCodeWait() waits until a key is pressed and returns its code. The documentation for the gconsole module can be found in the TigerJython menu under Help / APLU documentation. |

ENUMERATIONS AS STATE AND EVENT IDENTIFIERS |

Since the automaton operates with certain states, input values, and output values, it makes sense to introduce a particular data structure for that. Many programming languages offer a specific data type for enumeration. Unfortunately this data type is missing in the standard syntax of Python, but it can be added in TigerJython using the additional keyword enum(). You should use strings when defining the enumeration values, however they must adhere to the variable naming convention. from gconsole import * def getEvent(): keyCode = getKeyCodeWait() if keyCode == 38: # up return Events.stop if keyCode == 40: # down return Events.work if keyCode == 37: # left return Events.turnOff if keyCode == 39: # right return Events.turnOn return None State = enum("OFF", "STANDBY", "WORKING") state = State.OFF Events = enum("turnOn", "turnOff", "stop", "work") makeConsole() while True: gprintln("State: " + str(state)) event = getEvent() if event == Events.turnOn: if state == State.OFF: state = State.STANDBY elif event == Events.turnOff: state = State.OFF elif event == Events.work: if state == State.STANDBY: state = State.WORKING elif event == Events.stop: if state == State.WORKING: state = State.STANDBY

|

MEMO |

|

It is up to you whether you want to use the additional data type enum. The programs will not be shorter, but rather more clear and secure, since only enumeration values defined in the enum may occur. |

MOUSE-CONTROLLED IMPLEMENTATION OF ESPRESSO MACHINE |

from gamegrid import * def pressEvent(e): global state loc = toLocationInGrid(e.getX(), e.getY()) if loc == Location(1, 2): # off state = State.OFF led.show(0) coffee.hide() elif loc == Location(2, 2): # on if state == State.OFF: state = State.STANDBY led.show(1) elif loc == Location(4, 2): # stop if state == State.WORKING: state = State.STANDBY coffee.hide() elif loc == Location(5, 2): # work if state == State.STANDBY: state = State.WORKING coffee.show() setTitle("State: " + str(state)) refresh() State = enum("OFF", "STANDBY", "WORKING") state = State.OFF makeGameGrid(7, 11, 50, None, "sprites/espresso.png", False, mousePressed = pressEvent) show() setTitle("State: " + str(state)) led = Actor("sprites/lightout.gif", 2) addActor(led, Location(3, 3)) coffee = Actor("sprites/coffee.png") addActor(coffee, Location(3, 6)) coffee.hide() refresh()

|

MEMO |

|

A simulation becomes very clear and attractive with a graphical user interface. |

THINKING IN STATES WITH GRAPHICAL USER INTERFACES |

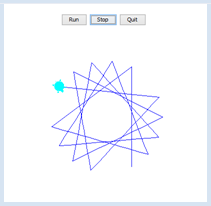

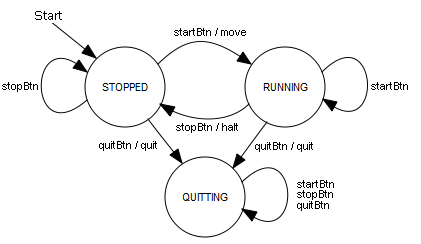

As you already know, no animations and only short-lasting code may be executed in GUI event callbacks, since the screen is only re-rendered at the end of the function. This is why in the callbacks of the button clicks you only modify the state, and you execute the movement of the turtle in the main part of the program. (You can learn more about this problem in Appendix 4: Parallel processing) from javax.swing import JButton from gturtle import * def buttonCallback(evt): global state source = evt.getSource() if source == runBtn: state = State.RUNNING setTitle("State: RUNNING") if source == stopBtn: state = State.STOPPED setTitle("State: STOPPED") if source == quitBtn: state = State.QUITTING setTitle("State: QUITTING") State = enum("STOPPED", "RUNNING", "QUITTING") state = State.STOPPED runBtn = JButton("Run", actionPerformed = buttonCallback) stopBtn = JButton("Stop", actionPerformed = buttonCallback) quitBtn = JButton("Quit", actionPerformed = buttonCallback) makeTurtle() setTitle("State: STOPPED") back(100) pg = getPlayground() pg.add(runBtn) pg.add(stopBtn) pg.add(quitBtn) pg.validate() while state != State.QUITTING and not isDisposed(): if state == State.RUNNING: forward(200).left(127) dispose()

|

MEMO |

|

This program structure is typical of event-driven programs and you should try to remember it well. You have to import the package JButton in order to use the buttons, and then add them to the turtle window (the playground) using add(). You have to re-render the turtle window using validate() in order to make them visible. |

EXERCISES |

|

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL |

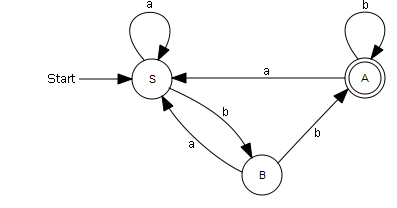

ACCEPTORS FOR REGULAR LANGUAGES |

A formal language consists of an alphabet of symbols and a set of rules, which allows someone to clearly decide whether a particular sequence of symbols belongs to the language. If it is possible to implement the set of rules using an automaton, it is called a regular language. As an example, look at a very simple language with an alphabet consisting only of the letters a and b. You can regard the set of rules as a special case of a Mealy machine that does not generate output values. In this case, the machine reads character by character starting at an initial state and transitions to a successive state based on the read character. If it is located in one of the predetermined final states after reading the last character, the word does indeed belong to the language. Look at the following transition graph (S: initial state, A: end state):In the implementation, the change of state is triggered by pressing the character keys a or b. Then, your program writes out the current state and the input word. from gconsole import * def getKeyEvent(): global word keyCode = getKeyCodeWait(True) if keyCode == KeyEvent.VK_A: return Events.a if keyCode == KeyEvent.VK_B: return Events.b return None State = enum("S", "A", "B") state = State.S Events = enum("a", "b") makeConsole() word = "" gprintln("State: " + str(state)) while True: entry = getKeyEvent() if entry == Events.a: if state == State.A: state = State.S elif state == State.B: state = State.S word += "a" gprint("Word: " + word + " -> ") gprintln("State: " + str(state)) elif entry == Events.b: if state == State.S: state = State.B elif state == State.B: state = State.A word += "b" gprint("Word: " + word + " -> ") gprintln("State: " + str(state))

|

MEMO |

|

An acceptor checks to see if a word belongs to a language. It is a special case of a Mealy machine without output values. The word does indeed belong to the language if you arrive at the end state A after reading all letters, beginning in the initial state S. For example, abbabb belongs to the language, whereas baabaa does not. |

EXERCISES |

|